16 Nov New York’s Early Supercop

Talk about ethnic profiling. Early in the 20th century, the New York City Police Department’s highest-ranking Italian-American officer estimated that perhaps one-fifth of his fellow countrymen in Manhattan were involved in criminal activity. And no one was more determined to reform the image of his fellow immigrants than he.

In “The Black Hand: The Epic War Between a Brilliant Detective and the Deadliest Secret Society in American History” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $28), Stephan Talty resurrects the engaging saga of Joseph Petrosino, who almost single-handedly battled prejudice within the department and suspicion from his countrymen, whom the Black Hand subjected to a reign of terror that the author likens to what black Americans faced from the Ku Klux Klan.

Mr. Talty, an author of narrative nonfiction and psychological thrillers, transforms would could have been another rehashed biography into an absorbing exploration of one man’s obsession to redeem his heritage amid familiar fears of foreigners.

Mr. Petrosino immigrated to the United States with his father in 1873 when he was 13; managed to apprentice himself to Clubber Williams, the notoriously tough cop from Manhattan’s Tenderloin district; graduated from the White Wings corps of street sweepers to the police force; became the first Italian-American detective sergeant; and insinuated himself into the thankless job of eradicating the Black Hand, the gang of kidnappers and extortionists who preyed on vulnerable Italian immigrants.

The tactics of his Italian Squad would have failed most First Amendment tests, but they got results. Mr. Petrosino, a master of disguises, even impersonated Enrico Caruso to recover his down payment for protection.

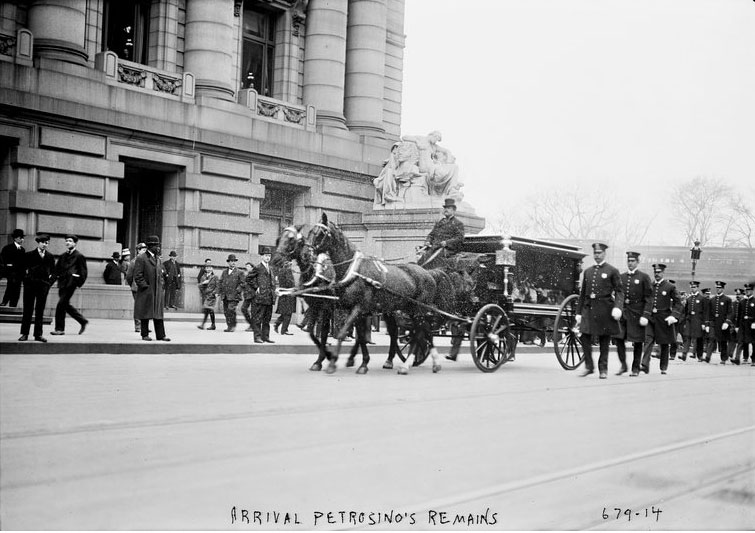

An estimated 250,000 New Yorkers lined the route from Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Little Italy to the cemetery in Woodside, Queens, more than would mourn Rudolph Valentino almost two decades later.

“A day comes when a man dies under circumstances so striking and dramatic that the brooding soul of the city is touched and its distracted attention riveted,” The New York American wrote. “The Italian citizens of New York entered yesterday into a new sense of fellowship in the all-embracing household of the civic life.”

In reviewing “Broken Scales: Reflections on Injustice” by Joel Cohen with Dale J. Degenshein (American Bar Association, $29.95), Sol Wachtler, a former New York chief judge, recalled how Chelm, the legendary city of fools, decided to cope with its criminal population.

Chelm’s mayor conducted a tour of various prisons, Mr. Wachtler wrote in The New York Law Journal, and found that half the inmates admitted their guilt, while the other half pronounced themselves not guilty. “So here in Chelm,” the mayor concluded, “we should build two prisons — one for those who are guilty, and one for those who are innocent.”

Judge Wachtler’s point was that, unlike Chelm’s citizens, most Americans believe that people who don’t commit crimes are either acquitted or aren’t charged in the first place. But as Mr. Cohen found in his 2014 “Blindfolds Off: Judges on How They Decide,” interviews with actual participants in the system reveal frightening imperfections.

Among the victims of injustice profiled in “Broken Scales” are Steven Pagones, the assistant prosecutor who is still awaiting an admission from the Rev. Al Sharpton that he was wrongly accused in the 1987 Tawana Brawley case; Abdallah Higazy, in whose hotel room across from the World Trade Center a transceiver was found after 9/11, but who had nothing to do with the attack; and Miriam Moskowitz, who was convicted of conspiring to lie to a grand jury during the Red Scare in a run-up to the Rosenberg atomic spy case on the basis of what appears to have been perjured testimony against her.

“When you look at how they handled their circumstances,” Mr. Cohen, a lawyer at Stroock, writes, “ask what you would have done in the same situation.”

Call us at: Tel. 917-544-2202

Call us at: Tel. 917-544-2202